Focused Ultrasound and Nanomedicine for Enhanced Drug Delivery Across the Blood-Brain Barrier: A Systematic Review

Written by: Kaleena Kanagarajan

Uploaded: November 6, 2025

Approximate Read Time: 15 Minutes

1. Introduction

One of the greatest challenges of treating Central Nervous System (CNS) diseases is not

successfully developing therapeutics, but rather bypassing the Blood-Brain Barrier (BBB) in

order to administer them. Although its purpose is to protect our brains from the many toxins and

pathogens that may enter our bloodstream, the BBB also prevents many drugs from entering and

treating it as well. 98% of small-molecule drugs and all large-molecule drugs cannot pass it,

creating a challenge in treating those who suffer from CNS illnesses. A proposed solution is to

pair Focus-Ultrasound (FUS) Technology and Microbubbles (MBs), which will temporarily open

the BBB, with Nanoparticles (NPs), which act as alterable capsules to deliver the drugs. This

review will examine literature on the design and application of NPs with FUS technology, as

well as identify research gaps which are yet to be addressed.

2. What is the Blood-Brain Barrier?

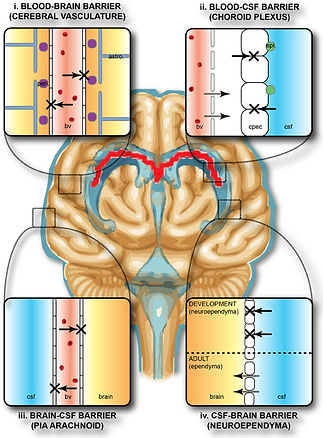

The blood-brain barrier (BBB) is a highly selective and protective semipermeable

membrane that coats the inner surface of the brain's blood capillaries. It is a complex structure

that has the role of safeguarding the sensitive chemical environment of the Central Nervous

System (CNS) from unwanted substances (Daneman & Prat, 2015). The barrier’s high selectivity

is due to its many layers of protection. The endothelial cells that line the capillaries are tightly

sealed together by complex tight junctions, preventing most water-soluble molecules from

squeezing between the cells, or in other words, taking the paracellular route. This forces substances to take the transcellular route, pass directly through the cell membrane, instead (Kadry et al., 2020). The barrier is further reinforced by surrounding cells, including pericytes and astrocyte end-feet, which regulate capillary permeability and function (Daneman & Prat, 2015). Necessary substances are allowed to enter the BBB through specialized active transport systems or maybe be able to just diffuse through depending on its composition. The lipid-based outer membrane allows small and nonpolar molecules to pass through, while blocking larger and polar molecules. Pardridge (2004) adds that drugs must be under 400-500 Da to pass through this membrane.

As previously mentioned, this high selectivity means that about 98% of all

small-molecule drugs and virtually all large-molecule drugs are not able to reach the CNS. The

BBB's impermeability to chemotherapy drugs is a main reason that glioblastoma, a highly

aggressive brain cancer, has one of the poorest prognosis, with limited development in extending

patient life expectancy (Meng et al., 2020). Furthermore, the overall failure of CNS drugs is

quantified by their significantly lower FDA approval rate, recorded at 6.7% between 1995 and

2007, compared to 13.3% for all non-CNS drugs (Gribkoff et al., 2016). This outlines a huge

problem in the medical field, which needs much research and attention to find a solution.

3. Nanoparticles (NPs)

The challenge of the BBB has established a critical need for an advanced drug delivery

system, which is where nanomedicine provides a solution. Nanotechnology manipulates atoms

and molecules typically between 1 nm and 100 nm in size. This amazing technology has the

potential to help developments in multiple fields, including medicine. In this case, NPs can be used as engineered carriers specifically designed to pass the BBB's defense mechanisms (Yusuf

et al., 2023). There are many different types of NPs, such as liposomes, micelles, and

dendrimers, each of which have unique physicochemical properties. Therefore, this technology is

very versatile and can be used for different situations. For example, a liposome can hold

hydrophobic drugs within its lipid bilayer, between the fatty acid tails, and hydrophilic drugs in

its aqueous core (Yusuf et al., 2023). These carriers can be further advanced with surface

engineering. PEGylation, the addition of polyethylene glycol (PEG) to the outer surface, is often

used. This coating creates a hydrophilic shield that tricks the immune system and prevents rapid

opsonization (when a foreign substance is marked for destruction by phagocytes), therefore

extending the bioactivity of the NP (Yusuf et al., 2023). Additionally, active groups, such as

folate or specific antibodies, can be added to NPs to facilitate receptor-mediated binding with

specific targets, increasing the targeting precision of this method. To sum up, the ability to

control an NP’s size, surface chemistry, and delivery mechanism makes these carriers a good

solution for bypassing the BBB.

Although nanocarriers can effectively address challenges related to drug stability and

targeted delivery, most NPs are still too large to cross the BBB. Their size typically ranges from

20-200 nm, making them substantially larger than the small molecules the BBB normally

permits. These small molecules usually have a molecular weight under approximately 500 Da

(Pardridge, 2004). Therefore, to reach the full potential of these sophisticated carriers, an

external physical method is needed to temporarily and safely open the BBB. This is where

nanomedicine combined with Focused Ultrasound (FUS) comes in.

4. What is Focused Ultrasound (FUS)?

Focus Ultrasound (FUS) is a method proposed to temporarily open the BBB in targeted

regions of the brain. As Burgess et al (2015) explains, microbubble (MB) contrast agents are

injected into blood vessels, where they will travel to the brain. Next, the focus ultrasound device,

with the help of MRI, will target the specific area of the brain where the medicine is needed.

Once the MBs have reached this region, the ultrasound waves will be applied, causing them to

expand and contract at the same frequency. This process is called stable captivation. The

oscillation of these bubbles will cause mechanical stress on the blood vessels, stimulating the

BBB to temporarily open up. Specifically, this oscillation will cause the tight junctions to loosen

up, creating gaps for drugs. This opening will only remain for between 6 and 24 hours, until the

barrier completely heals and returns to normal (Burgess et al., 2015).

MBs are stable in circulation for about 10 minutes and have a size of about 1-3 μm in diameter. They are composed of a core of non-polar gas and surrounded by shell-forming agents. As said by Durham et al (2024), MBs themselves have already been clinically approved in other settings and have little to no bioeffect on the body when used with FUS. But why do we even need them? Can we not just use FUS alone to open the BBB? Well, the MBs help to concentrate and amplify the amount of ultrasound energy that is applied (Burgess et al., 2015; Durham et al., 2024). In other words, the MBs almost act as catalysts, dramatically decreasing the amount of energy input required to open the BBB. If we were to use FUS alone, higher energy must be used to reach stable captivation, leading to skull heating, extensive tissue damage and many more permanent bioeffects. This said, there are specific parameters, such as acoustic pressure, which must also be controlled in order to prevent this damage and determine the extent of the BBB disruption (Burgess et al., 2015; Durham et al., 2024).

5. FUS Parameters

The success of FUS-mediated BBB disruption is directly dependent upon the frequency

and acoustic pressure of the FUS (Durham et al., 2024). These factors are adjusted to achieve the

desired therapeutic effect while maintaining safety.

6. Frequency

The frequency is crucial for both reaching the target region and ensuring safety by preventing overheating. Lower frequencies (200-500 kHz) are generally preferred for clinical settings because they experience less attenuation. This means the waves are less weakened as they pass through the brain to the target, ensuring they can apply the intended pressure upon arrival. On the other hand, high frequencies (≥ 1MHz) allow for more precise targeting and therefore can help prevent damage to unwanted areas. Unfortunately, they are attenuated more easily, which makes them unsuitable for deep brain targets, as more energy would need to be applied, risking skull heating. Clinical studies often utilize lower frequencies such as 0.22 MHz, 0.5 MHz, or 1.05 MHz, with 1.4 MHz generally considered the highest safe frequency. Therefore, when transmitting through the skull, lower frequencies are typically preferred. (Durham et al., 2024).

7. Acoustic Pressure

The acoustic pressure is a crucial detail in managing the safety and determining how big

the BBB opening will be. The acoustic pressure is the amount of local pressure that sound waves

can impose on a surface compared to the regular ambient pressure (101.325 kPa). This value is

often quantified as the Mechanical Index (MI) so that it can be compared between different

frequencies of FUS. Durham et al. (2024) explains that at lower pressures, the MBs can reach the

state of stable cavitation, where the BBB will open. Higher pressures will cause inertial

cavitation, where there might be a larger BBB disruption. Reaching this state is generally

undesirable, as the MB may also collapse and cause unwanted bioeffects. In order to prevent this,

a second ultrasound receiver is used alongside the FUS machine. It can detect the specific

responses MBs give for stable or inertial cavitation and give the operators real-time feedback,

increasing the safety. Furthermore, the applied pressure to reach these states is different for each

person due to many factors, like skull thickness and tissue properties. When FUS is applied, the

skull will absorb much of the energy applied. Therefore, high energies must be used for someone

with a thicker skull to get the correct pressure applied to the targeted region. Skull thickness of

the patient might be something that can be examined before the procedure, in order to increase

the safety and effectiveness of this treatment (Durham et al., 2024).

8. FUS-Nanomedicine Optimization

Now that we understand how NP drug delivery via FUS-mediated BBB disruption will work, how can we optimize it and ensure these two different concepts will work jointly? As mentioned above, NPs can be altered to fit any situation. Factors such as their size, all the way to their surface chemistry, can be changed to make sure they work (Yusuf et al., 2023). So we must now look into how these NPs can be manipulated to ensure the best outcome when paired with FUS.

To start, size plays a large role in the permeability of the NPs across the BBB. Although

the FUS will make it easier for particles to enter the CNS, we can help ensure that the drug-filled

NPs are passing through by investigating the impacts of size on permeability. Through in vivo

experiments with mice and in vitro experiments, Ohta et al. (2020) examined the permeability of

gold NPs between 3nm and 120nm, following the application of FUS. It was concluded that

although smaller particles have overall better permeability, medium-sized particles are better

suited for real-life applications. As supported by the vivo experiment, particles at the size of

15nm had the most efficiency as they were not or less likely to be removed by the kidney

compared to smaller particles. Ohta et al. (2020) hypothesized that the optimum size of NPs for

FUS-assisted delivery into the brain is determined by competition between permeation across the

gaps opened in the BBB and excretion from blood circulation.” Although there is still much

research to be done, this conclusion gives some insight into how the future of NP size might be

in order to optimize the outcome of drug delivery via FUS-mediated BBB disruption.

Next, we can look into how surface chemistry plays a role in the efficiency of NPs and

FUS. Ohta et al. (2020) mention how the large downside of NPs is that they cannot effectively

deliver to a target region, while Hersh et al. (2022) disputes that one of their greatest strengths is

the ability to alter their surface chemistry, allowing them to target specific receptors. As

previously mentioned, the addition of polyethylene glycol (PEG), as well as other ligands, can

help improve the efficiency of NPs (Hersh et al., 2022; Yusuf et al., 2023). Hersh et al. (2022) go into depth on how other ligands such as proteins, peptides, antibodies and surfactant can be used

in a “Trojan Horse” method for active targeting of specific receptors in the BBB. For example,

the transferrin receptor (TfR), which is abundant in BBB endothelial cells, can be tricked into

letting in NPs by adding ligands with high binding affinity to the receptor. Furthermore, by

choosing specific ligands, different regions of the brain with an abundance of the corresponding

receptors can be targeted (Hersh et al., 2022). Through further testing and development, different

regions can be simply targeted by adding specific ligands, improving the overall outcome of drug

delivery to specific targets.

9. Preclinical Models

Now that the FUS-nanocarrier method has been fully established, how promising is it with actual CNS diseases? It is necessary to examine the clinical promise of this method through preclinical CNS disease trials. For example, trials for Alzheimer's Disease (AD) have had highly positive results. Since the accumulation of Amyloid beta (Aβ) is a defining characteristic of AD, preclinical studies have focused on targeting Aβ plaques. When anti-Aβ antibodies are paired with FUS-mediated BBB opening, trials successfully show reduced Aβ amounts (Kong & Chang, 2023). Unexpectedly, FUS alone was also found to reduce Aβ amounts and even restore memory and cognitive function in animal models (Kong & Chang, 2023). This puzzling finding suggests FUS is not just a tool for delivery, but has the potential to become a treatment itself. Ultimately, FUS, even as a standalone, has proven its potential through preclinical trials and is ready to be further optimized with nanocarriers.

10. Gaps

Through extensive research, it has become clear that drug delivery via FUS-mediated

BBB disruption with MBs has much potential to help treat CNS illnesses, but there is still much

research to be done concerning the safety and application of this method. To start, although there

are many positive results of this method of treatment, there is not much information on its

long-term impact. After multiple disruptions, is it possible that the BBB may start to lose its

integrity? What if the reversibility of the disruption decreases after multiple uses? Is it possible

that this treatment could permanently compromise the CNS? Looking into the long-term effect of

the treatment is a crucial part of ensuring it is a practical solution which can be used. Next, we

can also look into how opening the BBB alone can have a negative response. The BBB has the

role of keeping the sensitive environment of our CNS safe. If this method opens this barrier, who

is to say that toxins and other pathogens will not enter the CNS along with the NPs? Following

the disruption, there will be a “window of vulnerability” during the approximate 24 hours it takes

to heal after the disruption. How can the CNS of the patient be protected during this time? More

research on the probability of something like this happening must be done, and a protocol must

be developed to protect the patients during this time frame. Finally, there is still so much we do

not know about this treatment. For example, as Kong & Chang (2023) examined, standalone

FUS somehow helped treat Alzheimer's. As of now, there is no explanation as to why this

response occurred. Although it might have been a positive result in this case, it is unknown what

sort of unexpected negative responses can occur as well. Therefore, there is much research to do

on the impact of this treatment before it can be safely used in humans.

11. Conclusion

The combination of Focused Ultrasound and nanomedicine has the potential to change

the game in terms of drug delivery to the Central Nervous System. By utilizing the mechanical

oscillation of microbubbles, FUS safely loosens the tight junction of the BBB, effectively

creating gaps for perfectly engineered NPs to slip through. After reviewing many sources, it has

proven to be safe and reversible but also highly adaptable, allowing for the delivery of many

different therapeutics to precise regions of the brain.

Despite the potential of this method, FUS-nanomedicine faces three main knowledge

gaps which must be addressed prior to clinical application: long-term impacts on the BBB’s

integrity, risk of the “window of vulnerability”, and explanations for the unknown biological

effects.

The future of this treatment must therefore focus on precision and protocol. While the

general range of parameters, such as acoustic pressure and frequency to achieve stable cavitation

is known, this data must be tuned for real-life applications. This requires in-depth experiments of

this method and developing a pre-procedural protocol to determine the optimal range of

parameters for each patient. Ultimately, through collecting detailed and precise data, as well as

developing proper application protocols, this technology can revolutionize the way CNS illnesses

are currently treated.

12. References.

Burgess, A., Shah, K., Hough, O., & Hynynen, K. (2015). Focused ultrasound-mediated drug

delivery through the blood–brain barrier. Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics, 15(5),

477–491. https://doi.org/10.1586/14737175.2015.1028369

Daneman, R., & Prat, A. (2015). The Blood–Brain barrier. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in

Biology, 7(1), a020412. https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a020412

Durham, P. G., Butnariu, A., Alghorazi, R., Pinton, G., Krishna, V., & Dayton, P. A. (2024).

Current clinical investigations of focused ultrasound blood-brain barrier disruption: A

review. Neurotherapeutics, 21(3), e00352. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neurot.2024.e00352

Gribkoff, V. K., & Kaczmarek, L. K. (2016). The need for new approaches in CNS drug

discovery: Why drugs have failed, and what can be done to improve outcomes.

Neuropharmacology, 120, 11–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropharm.2016.03.021

Hersh, A. M., Alomari, S., & Tyler, B. M. (2022). Crossing the Blood-Brain Barrier: Advances

in nanoparticle technology for drug delivery in Neuro-Oncology. International Journal of

Molecular Sciences, 23(8), 4153. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23084153

Kadry, H., Noorani, B., & Cucullo, L. (2020). A blood–brain barrier overview on structure,

function, impairment, and biomarkers of integrity. Fluids and Barriers of the CNS, 17(1),

69. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12987-020-00230-3

Kong, C., & Chang, W. S. (2023). Preclinical Research on Focused Ultrasound-Mediated

Blood–Brain Barrier Opening for Neurological Disorders: A review. Neurology

International, 15(1), 285–300. https://doi.org/10.3390/neurolint15010018

Meng, Y., Hynynen, K., & Lipsman, N. (2020). Applications of focused ultrasound in the brain:

from thermoablation to drug delivery. In Nature reviews & Neurology, Nature Reviews [Journal-article]. https://buzaevclinic.ru/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/10.1038@s41582-020-00418-z.pdf

Ohta, S., Kikuchi, E., Ishijima, A., Azuma, T., Sakuma, I., & Ito, T. (2020). Investigating the

optimum size of nanoparticles for their delivery into the brain assisted by focused

ultrasound-induced blood–brain barrier opening. Scientific Reports, 10(1), 18220.

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-75253-9

Pardridge, W. M. (2004). The blood-brain barrier: Bottleneck in brain drug development.

NeuroRx, 2(1), 3–14. https://doi.org/10.1602/neurorx.2.1.3

Yusuf, A., Almotairy, A. R. Z., Henidi, H., Alshehri, O. Y., & Aldughaim, M. S. (2023).

Nanoparticles as Drug delivery systems: A review of the implication of nanoparticles’

physicochemical properties on responses in biological systems. Polymers, 15(7), 1596.

https://doi.org/10.3390/polym15071596