Designing Red Blood Cell-Derived Vesicle Natural Killer Cell Engagers for Agnostic Cancer Treatment

Written by: Mengqi (Kathy) Han

Uploaded: August 1, 2025

Approximate Read Time: 8 Minutes

Selected for: 2025 Canada-Wide Science Fair

Won: Silver Medal

A PROJECT REPORT

1. Introduction

Immune cell engagers (ICEs) are an emerging feasible alternative to adoptive cell therapy that utilizes modified molecules to redirect immune effector cells (IECs), targeting specific tumour associated antigens (TAAs) on cancer cells. Conventional FDA-approved ICEs mainly consist of CD3+ T cell engagers (Shi, 2024), as the idea of T cell therapy is much more explored than any other adoptive cell therapies. However, despite its noteworthy performance, current T cell therapies face challenges like severe side effects (e.g., cytokine release syndrome (CRS), graft-versus-host disease (GvHD)), limited efficacy in solid tumours, manufacturing complexity, and risk of cancer relapse (Gershenson & Mello, 2022).

Natural Killer (NK) cell therapy, introduced in 2005 (Karolinska Institutet, n.d.), brings an advantage over T cell therapy as an alternative functional type of immunotherapy. NK cells are cytotoxic lymphocytes that target diseased cells without prior priming, enabling “off-the-shelf” use and compatibility for patients ineligible for traditional T cell therapy. Early correlative research also highlights the integral trait of NK cell therapy in bypassing immunosuppressive tumor microenvironments (TMEs) (Lian et al., 2021), underscoring again the advantages of NK cell therapy against other IEC therapies. However, NK cell activation relies on multi-step signaling, and cancer cells can appear refractory to NK cell recognition by downregulating activational ligands like MHC class 1 molecules, reducing immunosurveillance, promoting metastasis, and rendering the adaptive immune system ineffective (Seliger & Koehl, 2022). Such resistance remains a key limitation for NK therapy.

In recent years, specialized bispecific antibodies engineered to target NK cells and cancer cells have shown success in facilitating engagement and NK cytotoxicity. Yet, their clinical application is restrained by on-target, off-tumour toxicities due to their availability for binding of a singular activating ligand. Such bispecific antibodies are constrained to target a specific type of cancer, limiting their broader applications.

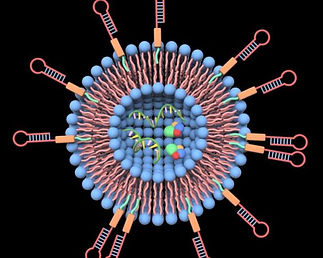

One of the biggest challenges in immunotherapy is the complete eradication of solid tumors.To address the problem of comparing solid tumours, and improving treatment efficacy through passing of the tumour microenvironment (TME), patient red blood cells (RBC) are used to produce minuscule vesicles as a biocompatible delivery system. A tumour’s TME consists of a complex matrix of non-malignant and immune cells, all of which are critical factors in cancer pathogenesis. Whether tumour suppressive or tumour supporting, the TME is one of the biggest obstacles in efficient therapy delivery to solid tumors. RBC-derived vesicles overcome these issues by utilizing RBC’s biocompatibility, abundance, biomimetic qualities, prolonged circulation, and TME bypassing via their natural membrane composition. The expression of the CD47 inhibitory signal on RBCs allows binding with signal regulatory protein-α (SIRPα) to avoid phagocytosis, enhancing the overall vesicle persistence against the immunosuppressive TME.

In this project, we aim to address these limitations in current immunotherapy by designing a biocompatible red blood cell (RBC)-based vesicle delivery system for NK cell engagers, aiming to integrate NK activational antibodies (anti-CD16, NKp46) and a tumour associated antigen (TAA) recombinant protein, rVAR2, for enhanced and histology-agnostic NK multifunctional engager functionalities, capable of preventing “off-target” cytotoxicity while ensuring cancer-specific targeting. In phase 1 of this project, RBC vesicles are to be produced and characterized for appropriate sizing, along with being labeled with 6-azido hexanoic acid NHS click chemistry reagent for later phase 2 NK activating antibody and TAA conjugation

2. Materials and Methods

a. RBC-vesicle generation

Whole blood was collected in EDTA tubes and processed within 24 hours of collection. RBCs were isolated from peripheral blood using Ficoll density gradient centrifuge (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The isolated RBCs were then harvested to be lysed progressively with hypotonic solution (1:3 PBS 1x with ddH2O) to release hemoglobin as the sample was set on ice for 30 minutes. The resulting RBC ghosts were washed four times with cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to ensure complete hemoglobin and RBC ghost separation (whitish pellet). The sample was spun at 14,000 G at 4oC for 5 minutes and lysed again with hypotonic solution. Sample was washed again with cold PBS, repeating two times until an RBC ghost pellet was observable enough for collection. This state of the vesicles is termed micro-erythrocytes (MERs) and was to be lysed further using ultrasonic energy into nano-erythrocytes (NERs). To perform this, MERs were diluted with PBS and sonicated at 40% amplitude for 5 min with a 1-second on, 1-second off cycle, for 5 minutes performed in triplicates, to disrupt the ghost membranes into nanoscale vesicles (NERs), performed by a sonicator. The resulting NERs were crude spun at 16,000 G for 20 minutes and stored at -80oC overnight for later characterization, using a zetasizer to obtain zeta potential and particle mobility through Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS).

b. Labeling with 6 Azidohexanoic Acid NHS Ester Click Chemistry Reagent

To adjoin cancer-spressive molecules to the RBC-vesicle membranes, the NHS-DBCO click chemistry linkage was used for stable conjugation. The bifunctional linker enables conjugation of molecules by using a linker with two reactive groups. The NHS ester reacts selectively with primary amines present on the RBC-vesicle membrane. The DBCO group undergoes a strain-promoted alkyne-azide cycloaddition (SPAAC) with azide-functionalized antibodies. NHS stock was diluted with dymethylsulfoxide (DMSO) to obtain a 500 μM working solution, which was then incubated with NERs mixture for 2 hours to allow NER-NHS-specific labeling. A Percoll density gradient was prepared by layering 100 μl of 50% Percoll at the bottom of Eppendorf tubes to prevent aggregation of NHS-labeled vesicles when spun for 50 minutes at 20,000 G (Fig. 1). The supernatant layer was collected at best and stored for later characterization.

Fig 1 - Density gradient centrifuge process for isolating NHS-labeled NERs

Protein quantification was performed using the bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific), which measures Cu2+ reduction Cu1+ from by peptide bonds, producing a purple color proportional to protein content. Results of the BCA assay were identified on a spectrophotometer at a wavelength of 562 nm and calculated using a standard curve. Flow cytometry was used to confirm NHS incorporation on NERs. As the flow cytometer relies on fluorescent expression for detection, a fluorescent secondary tag (DBCO-488) was stained with NER-NHS at 5 μM and incubated for 30 minutes to allow conjugation and minimize non-specific binding. Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) and compensation beads (Fisher Scientific) were prepared as controls. Residual DBCO-488 was washed off and resuspended in PBS before running flow cytometry.

3. Results

a. Nanovesicle Sizing using Zetasizer

The size of the NERs was determined using dynamic light scattering with the Zetasizer Nano ZS and was performed at 25oC in a sizing cuvette. The Z-average hydrodynamic diameter was 995.4 nm, with a polydispersity index (PdI) of 0.135, indicating a relatively uniform size distribution of NERs. The primary peak by intensity was at 1161 nm, accounting for 100% of the detected NERs, suggesting the sample was relatively homogeneous in terms of size populations. The standard deviation was shown to be 460.9 nm, which quantifies the spread of vesicle size around the primary peak of 1161 nm (1161 ± 460.9 nm).

b. NHS Conjugation Validation through Flow Cytometry

Flow cytometry was used to validate the presence of NHS labeled on the nanovesicle surface, using a fluorescent secondary, DBCO-488, as a fluorescent marker. NER-NHS stained with DBCO 488 was compared against NER-NHS unstained, which served as a negative control. FITC-labeled compensation beads were used to establish baseline fluorescence. As shown in Fig. 2, analysis in the FL6-A channel (FITC-A) showed a total of 3212 events recorded for stained NER-NHS and a total of 673 events for unstained NER-NHS. The fluorescence intensity distribution demonstrated an increase for stained NERs, with a peak around 10^3, compared to the unstained groups of NERs, which peaked around 10^3- 10^3, accompanied by debris at 10^0. This shift in fluorescence is an indicator of validation of the present NHS linker labeled on NERs.

Fig 2 - Histogram showed DBCO-488 expressed fluorescence intensity of stained (NER-NHS-DBCO488) and unstained (NER-NHS)

4. Discussion

The Zetasizer analysis determined a Z-average diameter of 995.4 nm for the NERs, with a low PdI of 0.135, suggesting a relatively uniform size distribution. However, this size exceeds the most optimal sizing range (Anselmo et al., 2014 suggest 100–200 nm for optimal delivery) for drug delivery and transmission of cancer suppressive molecules, increasing the chance of getting cleared by the reticuloendothelial system (RES) and limiting its performance of tumor penetration due to the permeability and retention (EPR) effect. The max size distribution peaks at 1161, with a standard deviation of 460.9 nm, suggesting possible aggregation and incomplete vesicle formation. Optimizing NER synthesis conditions, such as increasing the sonication amplitude, would potentially reduce Z-average for more effective NER biocompatibility and therapeutic applications. Flow cytometry validated NHS conjugation of the NER surface, as proved by a fluorescent shift in the DBCO-488-stained NERs (mean intensity ~10^6, n=673) in comparison to unstained controls (mean intensity ~10^3–10^4, n=3212, p<0.05). This shift indicates high conjugation efficiency of the stained group, suggesting successful NHS labeling. However, the overlap in fluorescence intensities between both groups, with minimal NER expression across both groups, depicts a heterogeneous mix of NHS-conjugated NERs and NHS-unconjugated NERs, likely due to incomplete labeling. The dramatic disparity in even counts (673 v.s 3212) reflects incomplete NHS and DBCO-488 staining and ineffective debris removal and contamination.

5. Conclusions

In this study, we completed Phase 1 by developing biomimetic NERs from isolated patient RBCs through hemoglobin removal and reduction of cell size via sonication, in an attempt to design vesicles in the nanoscale. NHS click chemistry linkage was labeled to the NER surface for testing of future molecular delivery. Zetasizer analysis revealed a uniform size distribution (Z-average 995.4 nm, PdI 0.135), though the large size suggests optimization is needed for better tumour penetration. Flow cytometry was performed to confirm NER-NHS conjugation, with DBCO-488-stained NERs expressing most fluorescence intensity (mean intensity ~10^6, n=673) in comparison to unstained controls (mean intensity ~10^3–10^4, n=3212, p<0.05), indicating successful NHS labeling, despite some heterogeneity. These findings were able to validate RBC-derived NER as a promising vehicle for delivering cancer-suppressive molecules to overcome the immunosuppressive TME. Optimization of NER synthesis will be applied to achieve better performance as a biocompatible, non-patient-specific delivery system for off-the-shelf therapies. This work sets the foundation for Project TRINKE 2025, which will design an RBC-derived NER-based multifunctional NK cell engager as a potential agnostic cancer therapy.

6. References

Ansari, Azim, et al. “Nanovesicles Based Drug Targeting to Control Tumor Growth and Metastasis.” Advances in Cancer Biology - Metastasis, vol. 7, July 2023, p. 100083, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adcanc.2022.100083. Accessed 19 Feb. 2025.

Cao, Wendy, et al. “Modification of Cysteine-Substituted Antibodies Using Enzymatic Oxidative Coupling Reactions.” Bioconjugate Chemistry, vol. 34, no. 3, 14 Feb. 2023, pp. 510–517, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.2c00576. Accessed 19 Feb. 2025.

Gauthier, Laurent, et al. “Multifunctional Natural Killer Cell Engagers Targeting NKp46 Trigger Protective Tumor Immunity.” Cell, vol. 177, no. 7, June 2019, pp. 1701-1713.e16, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2019.04.041. Accessed 19 Feb. 2025.

Jiang, Dandan, et al. “Driving Natural Killer Cell-Based Cancer Immunotherapy for Cancer Treatment: An Arduous Journey to Promising Ground.” Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy, vol. 165, Sept. 2023, p. 115004, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2023.115004. Accessed 19 Feb. 2025.

Khazamipour, Nastaran, et al. “Oncofetal Chondroitin Sulfate: A Putative Therapeutic Target in Adult and Pediatric Solid Tumors.” Cells, vol. 9, no. 4, 28 Mar. 2020, p. 818, https://doi.org/10.3390/cells9040818. Accessed 19 Feb. 2025.

---. “Oncofetal Chondroitin Sulfate: A Putative Therapeutic Target in Adult and Pediatric Solid Tumors.” Cells, vol. 9, no. 4, 28 Mar. 2020, p. 818, https://doi.org/10.3390/cells9040818. Accessed 19 Feb. 2025.

Murugan, Dhanashree, et al. “Nanoparticle Enhancement of Natural Killer (NK) Cell-Based Immunotherapy.” Cancers, vol. 14, no. 21, 4 Nov. 2022, p. 5438, https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14215438. Accessed 19 Feb. 2025.

Pickens, Chad J., et al. “Practical Considerations, Challenges, and Limitations of Bioconjugation via Azide–Alkyne Cycloaddition.” Bioconjugate Chemistry, vol. 29, no. 3, 29 Dec. 2017, pp. 686–701, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.7b00633. Accessed 19 Feb. 2025.

Seiler, Roland, et al. “An Oncofetal Glycosaminoglycan Modification Provides Therapeutic Access to Cisplatin-Resistant Bladder Cancer.” European Urology, vol. 72, no. 1, July 2017, pp. 142–150, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2017.03.021. Accessed 19 Feb. 2025.

Singh, Ajit, et al. “Overcoming the Challenges Associated with CD3+ T-Cell Redirection in Cancer.” British Journal of Cancer, vol. 124, no. 6, 19 Jan. 2021, pp. 1037–1048, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41416-020-01225-5. Accessed 19 Feb. 2025.

Vidal-Calvo, Elena Ethel, et al. “Tumor-Agnostic Cancer Therapy Using Antibodies Targeting Oncofetal Chondroitin Sulfate.” Nature Communications, vol. 15, no. 1, 30 Aug. 2024, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-51781-0. Accessed 19 Feb. 2025.

Wang, Chris Kedong, et al. “Internalization and Trafficking of CSPG-Bound Recombinant VAR2CSA Lectins in Cancer Cells.” Scientific Reports, vol. 12, no. 1, 23 Feb. 2022, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-07025-6. Accessed 19 Feb. 2025.

Yang, Xiao-mei, et al. “Nanobody-Based Bispecific T-Cell Engager (Nb-BiTE): A New Platform for Enhanced T-Cell Immunotherapy.” Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy, vol. 8, no. 1, 4 Sept. 2023, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41392-023-01523-3. Accessed 19 Feb. 2025.

Ye, Qian-Ni, et al. “Orchestrating NK and T Cells via Tri-Specific Nano-Antibodies for Synergistic Antitumor Immunity.” Nature Communications, vol. 15, no. 1, 23 July 2024, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-50474-y. Accessed 19 Feb. 2025.

Zhang, Minchuan, et al. “Natural Killer Cell Engagers (NKCEs): A New Frontier in Cancer Immunotherapy.” Frontiers in Immunology, vol. 14, 9 Aug. 2023, https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2023.1207276. Accessed 19 Feb. 2025.